BY JODI PETERSON

A water shoe, a plastic bag, a poop emoji. As each of these items were pulled out of a bag of ocean “pollutants,” ripples of laughter spread through the third-grade classroom. On this Friday afternoon in May, students at Hickam Elementary in Honolulu, Hawaiʻi were not just having fun, though—they were also learning a serious lesson about water pollution.

Teaching local residents and children how to take care of their Oʻahu home is the specialty of Angie Arroyo and Kristy Morris, employees of CSU’s Center for Environmental Management of Military Lands. As water programs support staff, they help Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam, an Air Force and Navy base, implement its stormwater program. Through this program, JBPHH safeguards marine life; keeps Pearl Harbor clean for water sports and fishing; and complies with federal water-quality laws.

Pearl Harbor was, of course, the site of the 1941 Japanese military strike that launched the United States into World War II. Today, the harbor boasts stretches of sandy beach and turquoise waters that are home to sensitive waterbirds, sea creatures, and plants. “Heavy metals and chemicals harm marine life through bioaccumulation,” said Morris. “Pollutants work their way up the food chain, through fish to the birds.” To help avoid that, she and Arroyo inspect base facilities, looking for anything that might create water pollution, such as open trashcans or improperly stored materials. Their main focus, though, is on public outreach, working with base employees and residents to show them how their actions on land can help—or harm—local beaches and ocean waters. “Public outreach and education about stormwater pollution prevention leads to better community support and improves compliance with the installation’s stormwater permit,” notes principal investigator Pete Jacobson, who oversees CEMML support for the JBPHH stormwater program.

Arroyo and Morris provide educational programs at local libraries and schools and work with adult volunteer groups. To make their presentations more exciting, the duo use props such as an EnviroScape® Watershed Model, which gives kids a hands-on way to see the causes and effects of water pollution.

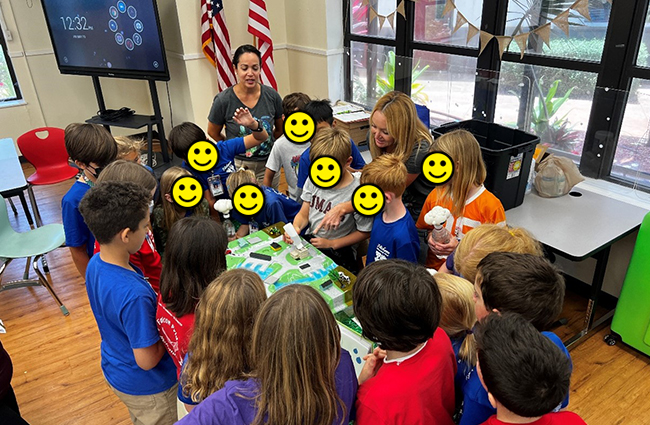

At the May event at Hickam Elementary, students first learned that rainfall picks up debris, chemicals, and other pollutants and carries them into storm drains that empty into the ocean. Then it was time to see that process in action. On the right side of the 3-D watershed model, which contained tiny plastic buildings, parking lots, and streams, the children placed “pollutants” such as confetti, green liquid, chocolate sprinkles, and soapy water. As they did so, Arroyo and Morris discussed the sources of those pollutants (for example, the chocolate sprinkles were stand-ins for dog poop; the green liquid represented lawn fertilizer) and their environmental impacts. Then the students used water bottles to make it “rain,” and the left side of the model, the “ocean,” filled with sudsy, discolored water laden with “marine debris.” “One of the exciting parts of this event was hearing the kids relate something they learned in school to what they saw happening in the model,” said Arroyo.

Another recent event involved the installation beautification group LOVE JBPHH. About 110 volunteers, both military and civilian, fanned out across the base and filled dozens of trash bags with old tires, scrap wood, discarded packaging, and more. Arroyo and Morris were on hand to talk about the installation’s stormwater system and explain that the group’s cleanup efforts would be documented as a step to improve water quality. “Everyone has a part in keeping pollution out of the stormwater that washes into the harbor,” said Morris. “We try to help people make the connection between things that they do, such as putting fertilizer on lawns and storing old tires outside, and the impact on water quality.”

Success is measured by the number of outreach events held (eight so far this year) and the number of people engaged (at least 380). They’re also expecting improvements in water quality metrics, although those will take longer to see since many JBPHH facilities are monitored only once every five years. “We’ve already seen changes, though,” said Morris, noting that an industrial facility the team inspected earlier this year is now storing tires under cover. She and Arroyo will continue their various outreach efforts; next they plan to have LOVE JBPHH and a group of young volunteers pull weeds and mark storm drains. “Our team has made great progress creating community connections,” Morris said. “We’ve got baseline data now, and over time we should see even more positive impacts on behavior and operations.”

At Hickam Elementary, Angie Arroyo breaks the ice with a fun quiz on water facts. Courtesy JBPHH.

At Hickam Elementary, Angie Arroyo breaks the ice with a fun quiz on water facts. Courtesy JBPHH.