BY JODI PETERSON

Snakes have gotten a bad rap. In literature and tradition, they’re usually villains. Think of the sly serpent in the Garden of Eden; sinister Kaa, the python in Kipling’s “The Jungle Book”; wicked Nagini, pet of dark wizard Voldemort in the Harry Potter series.

While many people react to snakes with fear and revulsion, others are working to change that perception, including staffers at Fort Johnson, an Army installation in Louisiana (formerly known as Fort Polk, its full name is now the Joint Readiness Training Center and Fort Johnson). The installation is home to one of North America’s rarest snake species, the Louisiana pinesnake, protected under the Endangered Species Act as threatened. Installation staff spend a lot of time educating soldiers and the public about snakes in general and the imperiled pinesnake in particular. They also study the pinesnake and work to improve its habitat and increase its numbers.

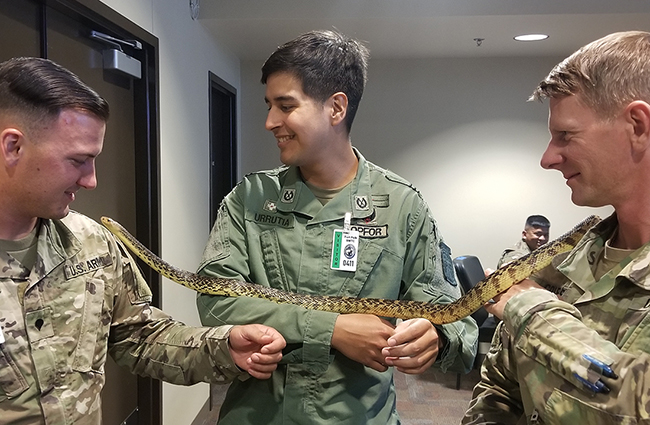

One of those staffers, Amy Brennan, is a conservation outreach specialist with Colorado State University’s Center for Environmental Management of Military Lands, which helps the Department of Defense manage natural and cultural resources on its lands. CEMML has a total of five staff members who help with threatened and endangered species conservation at Fort Johnson. Brennan has been there for about seven years, continuing the installation’s long-standing outreach efforts. She’s assisted by two scaly ambassadors, captive-bred pinesnakes Mario and Luigi. “We talk to at least 3,000 people each year at soldier briefings, as well as at local schools and camps,” said Brennan. “People see a lady holding a snake, and that helps them get over their fear and benefits their perception of all snakes.”

Brennan also trains the military officers responsible for ensuring Fort Johnson’s compliance with environmental laws. “We ask them to not harass or injure any pinesnakes they might see on the installation—just get a picture if possible, note the coordinates, and give us a call.” Those calls go to Brennan or to Chris Melder, supervisory wildlife biologist with CEMML at Fort Johnson since 1999. Melder then usually heads out to take a look, especially when a photo shows a possible Louisiana pinesnake. If he finds one, he tries to capture it to gather data and samples. The installation has been monitoring the species for 30 years, and in all that time its biologists have encountered less than 50 individual snakes.

A 4- to 5-foot-long constrictor marked with brownish-black splotches, the pinesnake is not dangerous to people, only to rodents—especially the Baird’s pocket gopher, which makes up three-quarters of its diet. Most of its time is spent underground, hunting in gopher burrows. While it lays the largest eggs of any North American snake, up to 5 inches long, each clutch has only a few eggs, so its populations increase slowly. It inhabits longleaf pine forests, but today, due to extensive logging, only about 3% remains of the 90 million acres across the South once covered by longleaf pine. Other threats to the species include snake fungal disease and housing development. The pinesnake occurs in just a handful of counties in Texas and Louisiana; both states protected the species for years before its federal listing in 2018.

Read more about Chris Melder’s “Cool Job” as a biologist in a recent magazine article

Installation biologists use several tools to study the pinesnake. Driving Fort Johnson roads is a simple way to see any snakes that are out and about. In the past, biologists used radio telemetry to track individual snakes, but that required catching an animal and implanting a tiny transmitter. Once the species was listed as threatened, this method could no longer be used because of the risk. Today Melder and others trap pinesnakes under a permit from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service that allows them to take blood and fecal samples to study.

The trick, though, is actually finding the elusive snakes. Because there are so few of them, thousands of hours of trapping may yield just one or two specimens. Remote cameras have similar limitations; getting a picture of a pinesnake is a rare event indeed. So Fort Johnson biologists are using a cutting-edge technology to gather data—eDNA. Environmental DNA gives researchers a non-invasive way to study pinesnakes by testing soil samples for traces of their genetic material, such as skin cells and saliva. Positive results show that pinesnakes have been in a particular location. That information helps the installation plan management efforts and ensure that military training and construction activities don’t harm pinesnake habitat.

In addition to gathering data, Fort Johnson staff work to improve that habitat. Selective thinning and burning keep fire-dependent longleaf pine forests in prime condition so that they support thriving populations of those all-important gophers. The fires clear out small trees and bushes and allow grass to grow; the gophers eat the grasses’ tender roots. Burning also benefits another endangered species on Fort Johnson that relies on mature longleaf pine, the red-cockaded woodpecker. “A nice, open, park-like pine savanna provides optimal conditions for the gopher and the pinesnake,” said Melder. “The snake might even like less dense forests, but we have the woodpeckers to consider as well, so we manage the forest in a way that works for all of them.” This management also benefits soldiers who train at Fort Johnson, by making the landscape easier to navigate and maneuver in.

Fort Johnson also works with a pinesnake stakeholder’s group that includes private landowners, timber companies, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the U.S. Forest Service, state wildlife departments in Texas and Louisiana, and nonprofits such as the Longleaf Alliance and the West-Central Louisiana Ecosystem Partnership. Participants share knowledge and cooperate on projects to conserve the snake wherever it’s found. The installation plants 300 acres of longleaf pines each year with funding from the National Wild Turkey Federation. It also provides wild-caught snakes to the Memphis Zoo, which extracts semen from the snakes, freezes it, and then returns the snakes for release where they were captured. The frozen semen can be used to increase the genetic diversity of pinesnakes at the four zoos that currently breed captive specimens. “This is one of the few reptile species for which we have the entire known studbook,” said Melder. “We know the exact genetic makeup and parents of every snake in the captive breeding program.” Hundreds of hatchling pinesnakes have been produced since 2010, and about 400 of them have been released in Louisiana’s Kisatchie National Forest. They’re now producing offspring of their own, an important step toward restoring the species.

Reflecting on the efforts to save the pinesnake, Brennan noted that attitudes are changing. “When I started at Fort Johnson, 30% of the audience was really hesitant to get near a snake,” she said. “Now it’s just 5%. People are learning that these less-than-loved creatures are still important and valuable and worthy of conservation.” Melder agreed. “In the 25 years I’ve been working here, the mindset of soldiers has definitely changed,” he said. “Back in the day, a grumpy old sergeant would have negative things to say about the Endangered Species Act. Now the young soldiers are easy to talk to about conservation. They realize that we’re on the same team, that wildlife conservation and the military mission are compatible.”

A Louisiana pinesnake on Fort Johnson. Courtesy Chris Melder.

A Louisiana pinesnake on Fort Johnson. Courtesy Chris Melder.