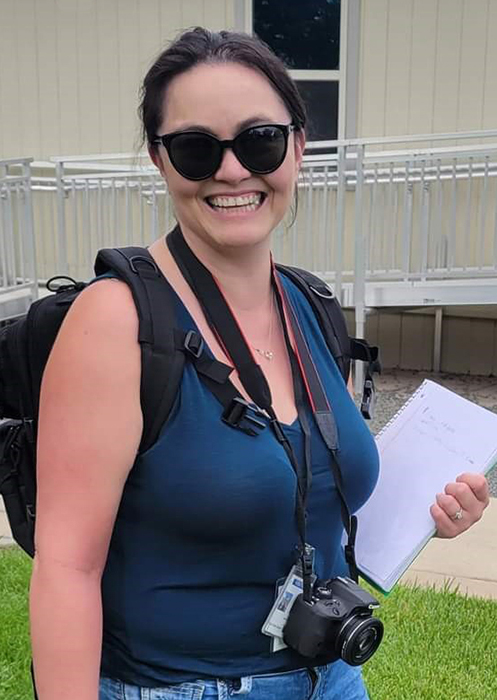

Alexandra Wallace is a Colorado native. Growing up in Fort Collins she was fascinated with history from a young age. After graduating from Colorado State University with a B.A. (2006) and an M.A. (2009), both in History, she has spent the last 13 years with CSU’s Center for Environmental Management of Military Lands (CEMML). Most recently, her roles have been Historic Preservation Specialist and Lead Architectural Historian, helping preserve the past for the Department of Defense. She recently sat down with CEMML Communications to talk about her background, her education, and the projects that continue to inspire her.

CEMML: You have both a BA and an MA in History from Colorado State University. What inspired your interest in history?

WALLACE: I can’t remember a time when I wasn’t interested in history. I remember sitting in my hometown library on the floor and reading and re-reading a book that showed a medieval city and its changes throughout time and I was hooked. I recall looking through my family’s encyclopedia and was drawn to the letter “C” in particular, since it showed clothing through different periods of history.

I’m a Fort Collins native, so I ended up going to CSU. I was originally going to study to become a writer of historical fiction, but I realized I didn’t love English in the same way. I fell in love with history in its own right, how it ebbs and flows, and how trends reach back and extend forward. So, I decided to go the B.A. path, because my mother was never gonna let me not go to school, that was just required. My Master’s program was my own choice.

CEMML: What were you trying to achieve through the Master’s program?

WALLACE: I originally went for the Master’s program with the intention to move on to a PhD program and eventually teach at the university level. But I was surrounded by other grad students, some of my dearest friends, who were able to grasp the theories so much better than I could. I felt like I had lost the fun of history, so I chatted with the graduate advisor, Dr. Janet Ore, who recommended looking at an emphasis in Public History.

“I liked that public history made history tangible. I learned to look at an item, a piece of furniture or a house or a landscape and see the history, trends, and ideologies in them.”

She introduced me to the non-thesis, public history track. At the time, I was thinking, “What the heck is public history?” She thought I’d be good at it since public history bridges the divide between academia and the public and doesn’t spend as much time in the ivory tower of history. The public history track provided multiple concentrations. One was historic preservation, another was archives, and the third one was museums. I ended up focusing on museum studies as well as historic preservation.

I liked that public history made history tangible. I learned to look at an item, a piece of furniture or a house or a landscape and see the history, trends, and ideologies in them.

CEMML: While you were studying at CSU, you didn’t know anything about CEMML, right? How did you eventually cross paths?

WALLACE: I was finishing up an internship at Rocky Mountain National Park in the summer of 2009 and I was attending one of the Public Lands History Center functions on campus because my internship was partially funded through them. Catherine Moore, who was part of my cohort, said she was working for Jim Zeidler, a director at this place on campus called the Center for Environmental Management of Military Lands (CEMML), which I had never heard of. She found out that I was leaving my internship because the funding had ended. Catherine knew Jim was going to need help and she asked if I would be interested.

So, I talked to Jim about working on an Integrated Cultural Resources Management Plan (ICRMP) for the U.S. Army Garrison for Hawaii. He gave me the spiel about CEMML and working in the military context and I think I understood about half of it. But I was a recent graduate without a job and so of course I said, “Yes, sir, I am happy to help!” I was grateful to join CEMML and help the cultural team with completing the ICRMP. After that, Jim found several other opportunities for me at CEMML, including cultural property protection projects, other ICRMPs, and historic building inventories.

CEMML: Do you get the opportunity at CEMML to do that more tangible work you mentioned?

WALLACE: Yes, definitely. At CEMML, most of what we end up doing is compliance-based, helping the military meet its legal obligations under federal and state laws. The federal government is required to consider the historic properties on its lands and CEMML is often tasked with evaluating buildings, structures, archaeological sites, and landscapes to determine if they are significant. Basically, we help sites learn how to best manage these properties. As a result, we are given the opportunity to go and look at so many properties on federal sites, particularly the military, and examine them for historic value. Maybe a site is significant because it has a building with a certain style of architecture, or it is associated with an important person or event.

For example, when I was working on a building inventory at Eglin Air Force Base in Florida, I surveyed a building at Duke Field. You wouldn’t think it was significant based on its appearance. But that’s where James Doolittle trained the Doolittle Raiders for a joint U.S. Army Air Corps/Navy bombing operation on major Japanese cities after the attack on Pearl Harbor. It is interesting to investigate buildings and see that they’re more than just brick and mortar, that they have a history. I like being able to see how they’re all connected within the landscape.

CEMML: I’m assuming a lot of your work focuses on military history specifically, but there are some sites that predate the military’s occupation of an area, right?

WALLACE: Interestingly enough, military installations end up being a great source for cultural resources for civilian and prehistoric sites, because they’re closed off for security purposes. Some amazing sites are within installations and have been protected.

For example, on Fort Drum in New York, communities lived there before the start of World War II when the military took over. There were houses, stores, mills, and cemeteries that predated the military’s presence, and the installation became responsible for recording them. They don’t have anything to do with the military, but they still are historically significant.

CEMML: Can you describe one of the most interesting projects you’ve worked on?

WALLACE: I am currently working on architectural inventories for the Idaho National Laboratory (INL) and Naval Reactors Facility (NRF) in Idaho. These facilities are in the middle of the Idaho desert, and so many of the reactors there were the first of their kind. The INL was established as the National Reactor Testing Station to design and test prototype reactors for nuclear research and to guide the development of future reactors. In 1951, the site’s Experimental Breeder Reactor I became the world’s first nuclear power plant. The station evolved and developed more reactors, with one producing so much energy that it could power the entire INL site with enough left over to sell to Idaho Power. Some reactors were developed to run safety tests. Other reactors were used in testing and deliberately pushed to runaway conditions before they were shut down. It seems a little scary, but very few accidents happened and they gained a lot of important information about reactors and their energy capabilities.

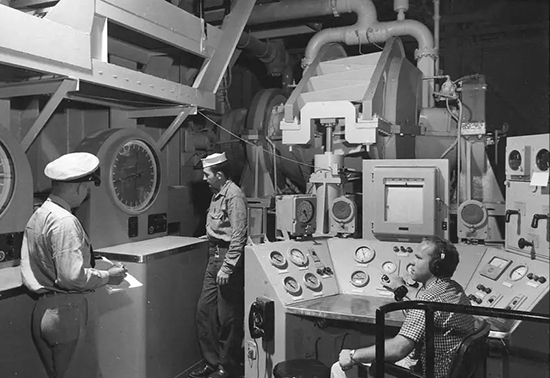

At the NRF, Navy personnel were trained to operate nuclear-powered submarines and carriers, the first in the world. Even though the Navy no longer uses these buildings to train seamen, these properties are incredibly historically significant. Many people who worked with these sites are still alive and still in the area. CEMML has been involved in interviewing several of these people and recording their experiences, especially since some information is no longer classified as the technology has changed. And so, these oral histories are tremendous historical resources that are going to be cataloged and shared with the Library of Congress and recorded for posterity.

Read more about CEMML and the Public Lands History Center’s Naval Reactors Facility Oral History Project.

Pictured: Monitoring equipment and water brake at the southern end of the S1W reactor prototype hull at the NRF in Idaho. The hull was used to train seamen on running nuclear powered submarines (Naval Reactors Facility Photo)

CEMML: Because the public doesn’t have access to them, military lands are relatively untouched both from an architectural standpoint and in terms of natural resources. Can you talk a little bit about the pros and cons of working within the military context?

WALLACE: If I was not working within the military framework, most of what I would end up looking at is only determining the local or national or industrial significance of a site or a building. But I also have the military framework to consider because the site may not be significant in any of these other realms. If it was militarily important because of certain testing that occurred there or because a certain group trained there, like the Doolittle Raiders, then it may become a significant site. A lot of people don’t think of the Department of Defense as being preservers, but in some ways, they can be, and they have effectively preserved some of their cultural assets in inspiring ways.

It can be challenging because of how the military maintains security on their lands. Like many other CEMML staff, I cannot tell you how many times I get asked, “What are you doing?”, as I’m walking through a military installation with a camera around my neck and a clipboard. And some people are just naturally curious, but I think that they have also been trained so heavily with the “if you see something, say something” mentality. The security is helpful because it helps preserve the spaces from outside damage, but at the same time it can be challenging because I’m just trying to do my job too.

CEMML: CEMML operates within the context of the military mission, which is to be prepared and ready to fight if called upon. Was reconciling that with your preservation expectations difficult?

WALLACE: Initially it was. I think I came out a little bit more doe-eyed from school and wanting to preserve everything. I quickly realized that the military, and most federal entities, can’t preserve everything, nor should they. There are plenty of things that are not architecturally important, especially if it’s just corrugated metal and it’s not significant. You could demolish it tomorrow and nobody’s going to miss it.

My approach is to work together to see what really is significant because maybe absolutely nothing is, and they can build whatever is needed. But, maybe over here, is where somebody’s home was, and it’s a great example of a Classical Revival house built by French immigrants, such as the LeRay mansion at Fort Drum, and that’s why it should be preserved. And if you put educational interpretive panels out front, that can also help fulfill your public outreach requirements. So, it’s finding ways to let cultural resources be tools for the military instead of hindrances.

CEMML: For somebody entering a cultural resources or historical preservation career, what are some things you think they should know?

For me, when I started at CEMML, I thought it was just going to be a temporary job. The work didn’t initially interest me, and so I would encourage recent graduates and those that are new to the field to not pigeonhole themselves. What interests you now may not be what interests you in the future, and sometimes you need to spend time working and figure out how what you learned can be applied to the field of preservation.

When I graduated, I wanted to focus on residential architecture and now I can’t imagine doing anything but federal landscapes and buildings. So, I would say take advantage of all the opportunities before you, because sometimes with compliance, we think it’s a boring requirement, but that’s also where great opportunities are. I would encourage folks to be broad-minded and open about their career possibilities.

With CEMML’s great breadth of locations, I have been able to travel and work at many different sites, including South Carolina, Florida, Alaska, Virginia, California, and Idaho. I’ve surveyed properties that I wouldn’t normally get the opportunity to visit, all while living in Fort Collins. I love it here. I was born here and can’t imagine living anywhere else.

Exterior and interior photos of Experimental Breeder Reactor I (EBR-I), the world’s first nuclear power plant, at the Idaho National Laboratory. (Photos by Alexandra Wallace)

Exterior and interior photos of Experimental Breeder Reactor I (EBR-I), the world’s first nuclear power plant, at the Idaho National Laboratory. (Photos by Alexandra Wallace)